Who are the Ismailis?

Ismailis are the second largest Shiite Muslim group after the Twelver sect (Athnā‘ashariyyah). They have witnessed an eventful history dating back to the middle of the second century AH—the eighth century CE—during the formative period of Islam. They have since split into several major branches and subgroups. Modern Yemen is acquainted with two of these main divisions, the Daoudi Ismailis (known also as Bohra) and the Sulaymaniyah Ismailis (Known also as Makaremah).

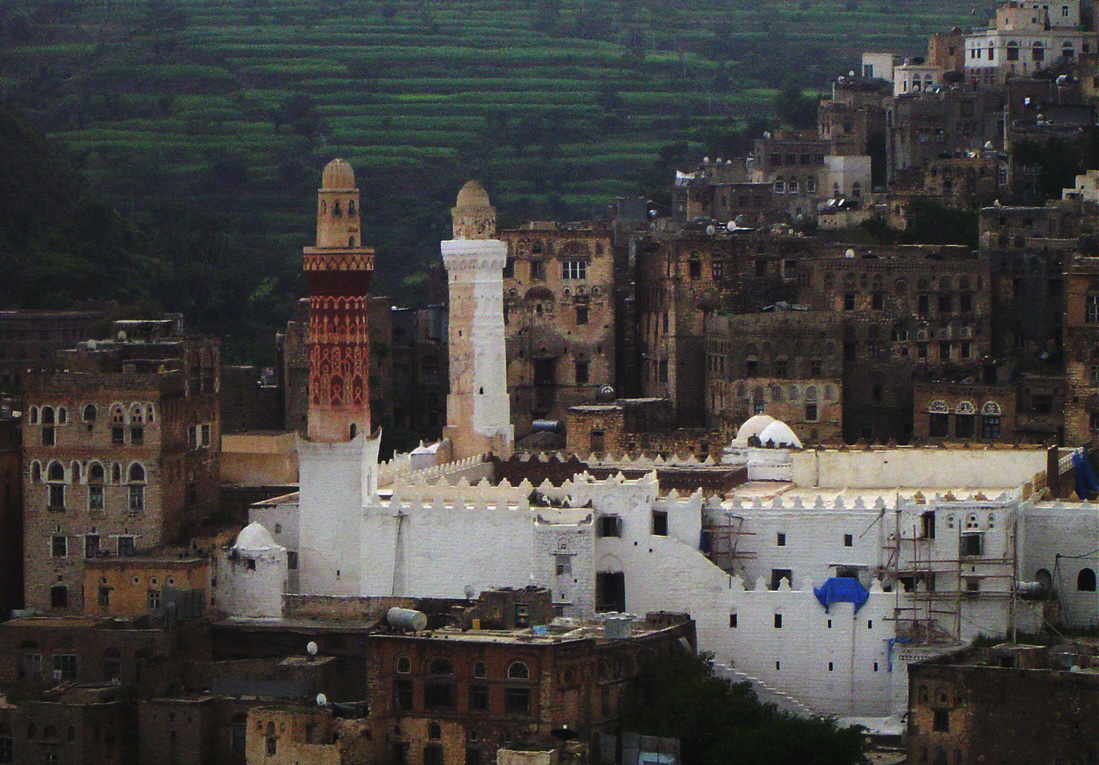

When Ibn al-Fadl conquered Sana’a in 293 AH/905–906 CE, almost all of Yemen fell under the control of the Ismailis, but they later lost most of the territories they conquered to the Zaydi Imamate and other local dynasties. With the death of Ibn Hushib (302 AH/924 CE) and the collapse of the Ismaili state in Yemen, the spread of the Ismaili teachings continued secretly for over a century, which is considered to be the dark period of Ismaili history in Yemen. Clandestine support for the cause continued to come from various tribes, especially the Hamdan tribe, and the names of its Yemeni preachers were kept secret. During the reign of the Fatimid caliph Al-Imam Al-Dahir (411–427 AH/1021–1036 CE), while the Zaydis and other local dynasties ruled Yemen, the preacher Sulayman ibn Abdullah al-Zawahi –who lived in the mountainous region of Haraz—was authorized to lead the spreading of the Ismaili teachings in Yemen. Suleiman Ali bin Mohammad Al-Sulaihi chose his successor, the son of the Judge of Haraz and an important Hamdani commander from the Yam clan who became the preacher’s assistant. In 429 AH/1038 CE, the preacher Ali ibn Mohammad Al-Sulaihi rose to power in Mazar, located in Haraz, where he built fortresses to mark the founding of the ruling Ismaili Sulayhid dynasty. With the support of the Hamdan, Hemyar, and several other tribes, Ali ibn Mohammad immediately began a swift campaign to conquer Yemen, which he was able to do in 455 AH/1063 CE.

After recognizing the sovereignty of the Fatimid caliph, Ali chose Sana’a as his capital and approved the sermon in the name of the Fatimid Ismailis throughout the territory under his rule. Hence, Ismailism in Yemen changed from a small religious sect, to the official religion of a full-fledged state that lasted for a considerable amount of time.

In addition to Haraz and Ibb in Yemen, Ismailis are also found in Najran, a fertile plain of land that stretches across the Saudi—Yemen border, and which came under Saudi rule in 1934. This is the spiritual center of the Sulaymaniyah Ismailis, with followers there numbering in the tens of thousands. Najran is also known for being the center of the supreme preacher of this sect. Their status in the region—with a few exceptions—dates back to 1640. Ismailis have lived in Najran for over a thousand years and were one of the many faiths that existed in early Islam. The Ismailis in Najran have social and religious relations with the rest of the Ismailis, both in Yemen and abroad in India, Pakistan and the rest of the world.

The Ismailis in Yemen are divided into two main denominations: The Dawoodi sect(also known as Bohra), named after their founder Dawood ibn Qutb, and the Sulaymani sect (also known as Al-Makarima in relation to the Makrami family in Najran). These two divisions were once one under the name Tayyibis, who believed that their line of Imams remained in the offspring of the Al-Tayyib. However, in the event of the absence of an Imam, the supreme preacher looks after the affairs of the Tayyibi sect and its community. As in the Imamate system, every supreme preacher chooses his successor before his death. The Tayyibis in Yemen were able to maintain their unity in the country, gaining increasing numbers of followers to their doctrine in western India. These were known as the Bohra, which is thought to be derived from the term Vohruvo, which means “to trade”, seeing that the spread of their teachings started among the Gajjar commercial group. After the death of the 26th supreme preacher Da’ud ibn ‘Ajabshah in 997 AH/1589 CE, a dispute over his succession led to the Dawoodi—Sulaymani division at the Musta’li Tayyibi University and its community. Despite the presence of followers of the two denominations in Yemen, the most prominent presence is that of the Dawoodi, who have many shrines and holy places that attract members of the sect from different regions around the world to Yemen.

Religion, Politics, and Their Integration into Society:

There are no official statistics that show the actual number of Ismailis, but according to a statement by the Ismaili Sheikh of Yemen, Ahmed Ali Abdullah Al-Mahalla, in an interview with Al-Mashhad Al-Yemeni, they number about half a million, and are based in Haraz in Sana’a, Arras, Al-Udain in Ibb, Waila in Sa’ada and to a lesser degree in Hamadan. However, these estimates lack any official confirmation, and appear to be exaggerated and are partly used for political reasons. According to INSAF researchers, who have reached out to prominent figures in the Ismaili community in Yemen, the Ismailis are actually estimated at 195,000, located as follows: 50,000 in Haraz, half of whom are Sulaymani and the other half Dawoodi; 15,000 in the area of Aras in Yarim, Ibb governorate, of which most are Sulaymani; 3,000 in the directorate of Al-Udain; 184 in the village of Tibah in Hamadan; and 45 in the village of Al-Amir. It should also be noted that several Ismailis live in the capital Sana’a, but they are originally affiliated with their area of Haraz or the rest of the areas to which they are still associated with.

Other than buying and selling, Ismailis social integration is virtually non-existent. Marriage only takes place between members of the same sect. They do not interfere in politics and have always had a good relationship with the rulers of Yemen. Their focus is mainly on religious and charitable matters, in addition to working in the field of trade. They have also been active in several community activities; they adopted and paid for a campaign to clean the streets of Sana’a in 2015. In 2018, they launched an initiative to replace qat trees with coffee trees in their main stronghold of Haraz by order of their current sultan, Mufaddal Saifuddin. The Dawoodi’s economic and societal activities are not limited to Yemen, but to wherever they are located in the world.

The Dawoodi sect is headed today by their 53rd preacher (Al-Mufadal ibn Mohammad Burhan Al-Din), and are mainly present in Haraz, about 90 km from Sana’a. The neighboring villages are home to the shrine of the sect’s preachers, where tens of thousands of Dawoodis come to visit each year. Of these shrines, is the tomb of Hatim ibn Ibrahim Al-Hamidi among many other shrines. In the capital Sana’a, the Dawoodi Ismaili community have a religious center in the Haddah area, known as Al-Faid Al-Hatimi. As for the Sulaymani Ismailis, they have a mosque in the Nuqum area, where they hold their ceremonies like the rest of their centers around the world.

Violations Against the Ismailis in Yemen:

Ismailis in general, and Ismailism in Yemen in particular, have been subjected to an ongoing stream of violence. This was helped by waves of continuous and systematic distortion by different sects and other religious groups, due to several factors as mentioned by the researcher Ahmed Abd Saif regarding the Ismaili sect. These include: the internal divisions within the same sect from time to time, their obscurity and the doctrine of taqiyya that raises questions and uncertainty, the secrecy of their philosophical and intellectual ideas which has kept their intellectual projects unpublished and away from the general public, and the continued political targeting of this group by successive governments and religious groups.

As a result of these hostile views and incitements towards followers of this doctrine, the Ismailis have been subjected throughout history to killing and extermination, with more than 50,000 Ismailis killed by the Zaydi sect during the days of Abdullah bin Hamza, Yahya bin Hamza, Mutawakkil, Hamid Al-Din and others. The sect has been subjected to many violations in the recent years, first through some of the preachers belonging to the Islah Party (Muslim Brotherhood) who consider the Ismaili’s teachings as blasphemy. This was followed of the Houthis, who in 2019 attacked Ismaili worshipers inside a mosque.

The war has created a fertile environment for extremist groups that are hostile to all of those who have different religious views. It also placed many obstacles in front of this community to practice its rituals, such as the visiting of shrines in both Haraz and Jableh, where followers of the sect used to come from different regions within Yemen and abroad. It has also now become impossible for many Dawoodi from outside Yemen, or those in areas far from the capital Sana’a (especially the southern regions), to perform their usual pilgrimages due to the closure of Sana’a International Airport by the Arab Coalition forces. Not to mention the obstacles faced by travelers on the road from areas under the control of the government of President Abdu Rabbo Mansour Hadi, to areas under the control of the Houthi group. This is in addition to the direct abuses they endure that threaten their lives and their freedom.

The Dawoodi have been affected by the repercussions of the ongoing war in Yemen since March 2015, which has led many members of this sect to leave the country. In 2015, a car bomb exploded in front of the Al-Faid Al-Hatimi center in Sanaa, killing at least three people. This center was previously raided by the Houthis and closed. In Aden, a Dawoodi businessman and his son escaped a kidnapping attempt by Islamic extremists in 2015. There was also an incident where the Saudi-led Arab Coalition forces detained a number of Yemeni Ismailis arriving from India, before releasing them. In a recent violation, an explosion was set off at the Al-Kawaja mosque in Aden. The most recent violation occurred this year (2019) where gunmen threatened the owner of the Remi restaurant (one of the most famous restaurants in the Crater area) to either pay money or close shop. These harassments, prosecution, and abuses have all led many of the Ismailis to leave Yemen from fear of themselves or their property being targeted by extremist groups operating under the insecurity and lawlessness the country is in at the moment, and the lack of a government that is able to protect minorities.